“His majesty slaughtered the armed forces of the Hittites in their entirety, their great rulers and all their brothers . . . their infantry and chariot troops fell prostrate, one on top of the other. His majesty killed them . . . and they lay stretched out in front of their horses. But his majesty was alone, nobody accompanied him. . . .”

–Temple inscription, Luxor, Egypt

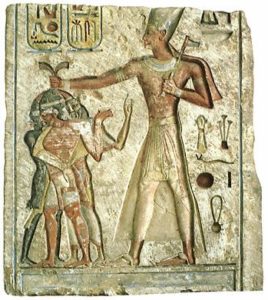

Ramses II heroically depicted single-handed taking Nubian war captives as slaves. Just one example among many of Ramses’ use art in serice of outlandish propaganda campaigns intended to enhance his prestige as pharaoh.

The bit of boasting quoted above is nothing short of a public relations move on the part of one of the most remarkable individuals to hold the Egyptian throne, Ramses II, who set out to do great things—and did.

Ruling nearly twice as long as any pharaoh before or after him, Ramses II began his reign in 1279 b.c. at the age of twenty-five. He ruled for over sixty-six years, and died at ninety-one, either of an abscessed tooth (common in ancient Egypt, where they had skilled physicians, but apparently not much in the way of dental care) or cardiac arrest.

Okay the gross stuff first.

Bastard (Double) Daddy:

Ramses had at least eight royal wives and any number of secondary wives, many of whom bore him children. Since Egyptian princesses were not allowed to marry anyone of lower social rank than they, it was common for them to marry brothers, cousins, even their fathers (in the Egyptian worldview, this form of incest merely doubled the “royalness” of any children born of two royal parents). Such was the case with Ramses and the first of several daughters he married, Bintanath, who bore him at least one child. There were others!

Yeah, so that whole “inbred royal” thing? The Egyptians started that. And their whole-hearted embrace of brother-sister/father-daughter royal marriage makes the Habsburgs seem almost like genetic mutts by comparison, huh? Of course, cultural context is everything, and Egyptian religion dictated that pharaonic blood was sacred, and as such, was not intended to be diluted with that of non-royals. (Cultural context aside, this little tidbit still makes you wanna say “Ewwww,” doesn’t it?)

Incidentally, this is the first monarch in recorded history to get fitted for the whole “the Great” nickname. Builder of cities and of monuments, conqueror of foreign lands, Ramses embraced being pharaoh with a gusto seldom seen before or since.

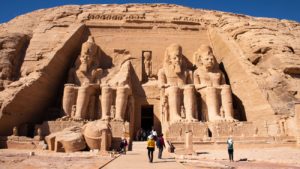

Three (originally four) colossal likenesses of Pharaoh Ramses II guarding the entrance to a temple dedicated to worshipping him as a god.

At places such as Abu Simbel in Nubia (near the present-day border between Egypt and Sudan), Ramses erected colossal statues of himself for visitors from outside of Egypt’s borders to see, admire, and most importantly, be intimidated by. At home, he impressed his own subjects in a similar manner with his massive temple complex at Karnak. He built a new capital city (named, of course, after himself) on the ruins of the former capital of the hated foreign invaders, the Hyksos, driven out of Egypt hundreds of years before his reign. The location was no coincidence: Ramses was showing the world that Egypt was now invading the world, not the other way round.

Some of Ramses’ most heavy-handed propaganda, from one of the walls of his temple at Abu Simbel: the Pharaoh himself, charging into battle alone, without so much as a driver for his royal chariot, and routing his Hittite foes-once again, single-handed.

This is pretty funny in light of the fact that Ramses’s greatest military victory was actually his worst defeat. Early in his reign, he set out to reconquer foreign territories that had been lost to neighboring countries, such as Syria/Palestine to the north and Nubia to the south. It was in Syria, at a place called Kadesh, that Ramses and his army, far from home, with their supply lines stretched thin, blundered into a trap set for them by their Hittite foes, an aggressive crowd who had extended their kingdom from Anatolia (present-day Turkey) into parts of Syria and Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq) and now threatened Egypt’s frontier holdings in Palestine and Jordan.

What happened next—according to Ramses—was a legendary victory. In reality, the Egyptian troops were routed. Ramses signed a peace treaty, went home and hyped the disaster as a great victory. In truth, he had lost thousands of troops in the slaughter at Kadesh, and this battle marked the end of his foreign military adventures.

Lying bastard!

Royal Poetic Inspiration:

![]() Ramses’ ancient propaganda campaigns intended to immortalize him in the minds of his people, was the inspiration for an unintended and ironic echo several millennia later. During the early 19th century English poet Percy Byshe Shelley (the husband of Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein) took in the ruins of several of Ramses’ statues with their boastful proclamations of the depth and breadth and extent of his awesome power, while on tour of Egypt and the Middle East. The vestigial remnants of the great king’s propaganda campaign served as inspiration for Ozymandias, one of Shelley’s most famous poems.

Ramses’ ancient propaganda campaigns intended to immortalize him in the minds of his people, was the inspiration for an unintended and ironic echo several millennia later. During the early 19th century English poet Percy Byshe Shelley (the husband of Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein) took in the ruins of several of Ramses’ statues with their boastful proclamations of the depth and breadth and extent of his awesome power, while on tour of Egypt and the Middle East. The vestigial remnants of the great king’s propaganda campaign served as inspiration for Ozymandias, one of Shelley’s most famous poems.

Like the monuments Ramses raised in his own name, the great king’s mummy also was not allowed to ride out the succeeding centuries gracefully. After the great king finally died in his early 90s from an abscessed tooth that eventually became infected, he was mummified and buried in his lavish royal tomb. Ramses’ tomb was repeatedly looted by grave robbers (likely the very workmen who had helped construct the royal tomb), and finally, several centuries after Ramses’ death and interment, the priests of Amun-Ra added his mummy to secret cache of royal mummies in a cave above the Valley of the Kings, where it lie hidden and forgotten until rediscovered in 1881.

The mummy of the once-great Ramses, discovered in 1881 at Dier el-Bahri, among a cache of royal mummies hidden by loyal priests hundreds of years after their original interment. Note this pharaoh’s distinctive red hard and hook nose. Ramses the Great: dead at age 91 or 92 of an abscessed tooth.